Take Five with Sara Moulton, On Life After the Demise of Gourmet Magazine

These days, Sara Moulton is almost a rarity among TV cooking show stars.

She’s a cook’s cook, a graduate of the prestigious Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, NY, who worked on the line at restaurants in Boston, New York and France for seven years, before becoming an instructor at Peter Kump’s New York Cooking School in New York, and finally executive chef of Gourmet magazine, where she worked until it unceremoniously ceased publication on October 2009.

Moulton, who lives in New York with her husband and two children, has been anything but idle since then. Her third cookbook was just published this month, “Sara Moulton’s Everyday Family Dinners” (Simon & Schuster). The book reinterprets what constitutes dinner and provides inventive, healthful fare to wake up that end-of-the-day meal.

You can meet Moulton at three upcoming Northern California events. She’ll do a cooking demo and sign copies of her new book at 11:30 a.m. May 18 at Sign of the Bear in Sonoma. For more information, call (707) 996-3722.

She’ll also do two cooking classes and book signings at Draeger’s markets: 5 p.m. May 18 at Draeger’s at Blackhawk in Danville; and 5 p.m. May 19 at Draeger’s in San Mateo. Tickets to either event are $80 per person.

I had a chance recently to chat with Moulton by phone about her new book, the changing culinary landscape, the shock of being unemployed, and the demise of the magazine we all loved.

Q: How did you find out that Gourmet was going to fold?

A: The magazine was way down in advertising pages, but so were many magazines at Conde Nast. We’d already been told we had to cut back 25 percent of expenses. We were already walking around, thinking, ‘Who’s next?’

We thought we were special — a jewel in the crown. We won all sorts of awards. We’d been going through a rough period, through many publishers, and we were way down in sales staff. We knew it was coming, but didn’t know it was coming.

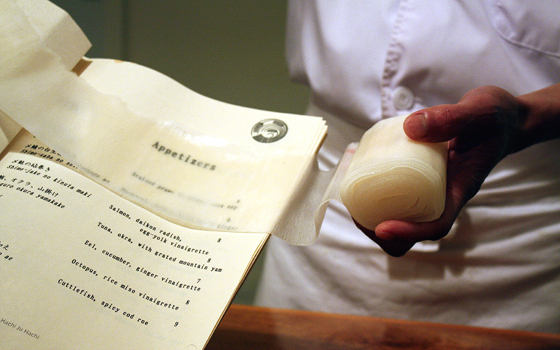

I’m not mad. I know Conde Nast had to make choices. I found out on a Monday morning, when I was out doing a photo shoot for my cookbook. We were at the farmers market with the photographer and had just gotten started. My cell phone rang at 9:30 a.m. It was my chef de cuisine, calling, and she was crying. I thought somebody had died. She said that they were shutting down the magazine, that there had been a meeting with the staff.

My immediate boss then called to tell me we had to have everything out by Tuesday at 5 p.m. It was quite a scramble.

Q: Where you able to pack up all the things that had been meaningful to you all those years?

A: My husband came to the office and helped me. We packed 35 boxes of books and shipped them home. I gave a bunch to Columbia University, and we built a new bookshelf in my son’s room.

I also took an old copper bowl, with Conde Nast’s permission. It’s from France, from the same cookware store that Julia Child used to buy her cookware from.

It’s a very heavy bowl. At my last restaurant job, I was the chef tourneau (substitute cook), who could work any station necessary. One thing I had to do at times was pastry, which was not my forte at all. We had an apricot souffle on the menu, made with dried California apricots, sugar, lemon juice and egg whites. We used to make the recipe by hand, whipping the egg whites by hand. We’d make seven souffles at a time.

On Saturday night that was my job. I’d have to make four or five batches. This bowl is a dead ringer for that bowl. The apricot souffle finally ran in Gourmet, and I also would teach people at classes how to do it by hand. The first time you whip egg whites or make bread, you should really do it by hand because you get a feel for it more. I didn’t want to leave that bowl behind. I didn’t want someone who didn’t care about it to just grab it and throw it out. It hangs in my kitchen now. I’m looking it as we speak.

Q: Your job at Gourmet was probably every foodie’s fantasy.

A: As the executive chef of the dining room, I cooked meals for the advertisers. We’d wine and dine them. Then, we’d hit them up for advertising. It used to work really well. (laughs). I was making the best food of my life in that dining room. It was a great job.

Q: Do you have a huge stack of Gourmet magazines at home?